NOTE: This is the second of two parts in a series about the Bransfords’ role at the cave, with the first being at this link. Due to complications arising from Friday’s winds and storms, it is being posted a day later. We apologize for the delay.

BY JENNIFER MOONSONG

GLASGOW NEWS 1

PHOTOS PROVIDED BY THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Mammoth Cave tour guide Jerry Bransford’s first memory in the Mammoth Cave National Park was in 1956, going back there with his family to the land they once called home, and eating ice cream.

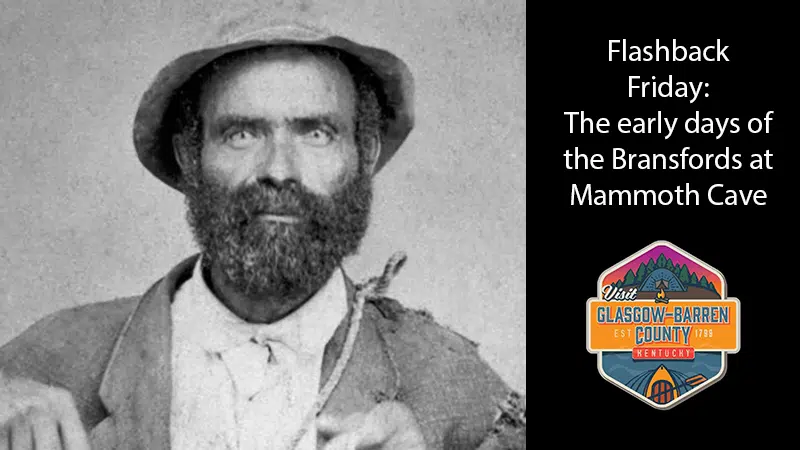

“I had to go the back door in 1956 to get an ice cream cone; all the black people did,” Bransford said. At that time, he had only heard his family speak of the legacy of the Bransfords at Mammoth Cave, but these days he tells the story often. It began in 1838.

In 1838, Franklin Gorin, for which the park in Glasgow is named, paid $5,000 for the cave and acres as a tourist attraction, wanting to have tours to attract people,” Bransford said. It was at that time Gorin bought a well-known slave by the name of Stephen Bishop.

“He was a smart and dynamic 17-year-old slave,” Bransford said.

Gorin needed more slaves to explore the cave and develop the land, though, so he reached out to Tennessee farmer Thomas Bransford.

Gorin rented two slave brothers, Nick and Matt Bransford, and they came to Mammoth Cave.

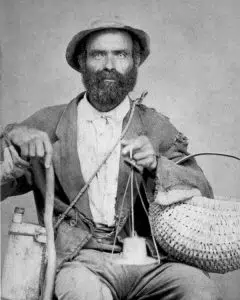

Matt Bransford, one of two slave bothers brought to Mammoth Cave, was one of the cave’s earliest explorers.

“Stephen Bishop taught them the tricks of the trade. Seemed like they were naturals at cave exploration and charting. I really think, according to how things were in slave days, the brothers had a unified place in society, even as slaves,” Bransford said.

The brothers and Bishop explored and advanced the uncharted caverns of the cave by candlelight and lanterns. It was six miles from the entrance they went through to what later became known as the Snowball Room.

“I can really only imagine the danger and risk of what they did,” Bransford said.

In 1857, a doctor named Cline from Louisville, a nephew of George Rogers Clark of the explorers Lewis and Clark, purchased the cave and land for $10,000.

“Tuberculosis, known back then as consumption, was raging, and the doctor wanted to find a cure,” Bransford said.

Cline erected a stone building inside the cavern known as the hospital.

“He believed breathing cave air revived and refreshed. Thought the cave air could improve consumption. The people who came there for this treatment were well to do. They would be confined to the dark, damp cave for months without being allowed to leave. I can’t imagine the sense of isolation, cold dampness. They looked like ghosts. The ghostly figures stumbled out asking what it was like outside because the cave doesn’t change; its always dark and always the same temperature,” Bransford said.

The patients start to pass away and kinfolk would come to collect them. Bringing in the cave air actually multiplied the negative effects of the consumption.

“Brothers Nick and Matt tried to tell the doctor he was killing people, but he told them to shut up because they did not know, but they stood up to the master and told him. Alfred, another slave, he told Cline, his free, white owner, it was killing people. He was told to keep his mouth shut, to not challenge him, a medical doctor, or he would be sold down the river,” Bransford said.

Later, times changed again and the Civil War came.

“They would see men in gray and men in blue and ask what it meant but were always told, “It doesn’t concern you,’” Bransford said.

Nick Bransford, brother to Matt, was responsible for exploring the depths of the cave along with his brother and Stephen Bishop.

Nick asked what it would take to be free, and he was told to raise $700. He raised the money a dime at a time taking people on tours, and the slave owner gave him his freedom papers.

“He goes to Nashville in 1863 only to find people treat you no different as a free man. Dad told me the story of how he went there and said it was no better being a free man working the fields, so he wanted to go home and work at Mammoth Cave,” Bransford said.

The war ended in 1865, but the times were still troubled with new challenges for free men.

Nick died in 1895. His brother Matt went on to be a businessman at Mammoth Cave.

“Before Nick passed away, he bought the land where the schoolhouse and Pleasant Union Baptist Church stand. Great-Uncle Matt saw the need for people and opened Matt Bransford’s Summer Resort. It had rooms and spring water. It was operated from 1923 to 1935. He married a woman named Zimmie,” he added.

The land of Mammoth Cave was inherently the land the Bransfords called home. But the formation of the Mammoth Cave Association and the development of the land left free black men without a place to live and the Bransfords were forced to move on, although they had no desire to do so. They distributed themselves throughout the region. Bransford’s father Jerry left the land at the age of 17, but always considered it to be home. Bransford grew up in Glasgow, attended the Ralph Bunche School and later Glasgow High School when segregation ended in the 1960s.

Brothers Matt and Nick Bransford explored Mammoth Cave.

Bransford went on to get a job with a company for which he worked for 30 years. Upon retirement, he was contacted by a friend, writer and tour guide at the cave, asking him to become a guide and tell his family’s story. He has been doing so for the past 19 years.

“I have no resentment in my heart. Everyone here treats me wonderfully, and I love my job. I see the names of my ancestors on the cave walls,” Bransford said.

In 2010, a section of the cave was dedicated to Bransford — Jerry Bransford’s Way. Just last year, a monument honoring the Bransfords was erected in the cemetery. It can be visited year round and will remain in the park as beacon to the legacy of those who explored the cave and made the exploration and education of thousands possible.

Comments