ADVERTISEMENT

Jennifer Moonsong

Glasgow News 1

This article is a paid promotion. The photos were provided by the ACCA.

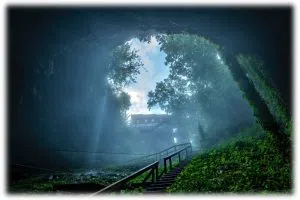

The entrance of Hidden River Cave, facing the museum, takes on an almost majestic appearance.

Submitted

Nestled in the heart of cave country, centered in the unassuming hamlet of Horse Cave, is Kentucky’s best hidden gem- Hidden River Cave. Driving down main street in the tiny town steeped in history, one would never think they are driving over the cavern, but they are. The vast rocky entrance of the cave, surrounded by an abundance of native heirloom plants, is practically hidden from those passing by, unless they happen to be on foot. Anyone taking time to peer closely into the depths surrounding the cave will see a distinguished pairing of the past and the present, with the practically crumbled staircase that was the original entryway for cave tours, but the history of the cave predates the town ten-fold, and no one understands the fascinating and enduring legacy of Hidden River Cave better than Dave Foster, whose legacy is the labor of love efforts to showcase the cave and its wonderful mystery, history and integral place in the natural world.

These days Foster, who is about four decades past the beginning of his ecological and geological journey, is a veritable encyclopedia when it comes to cave conservation. He could also pass for a local historian. Foster’s journey began in the early 80s, when he returned to college to Major in Geology.

“I majored in Music and minored in Geology at Emory & Henry College in Virginia, but later returned to Mary Washington to major in Geology,” Foster said. His interest in Geology stemmed from being an amateur cave explorer, and although most of his contemporaries were pursuing careers in the oil industry, Foster had his eye on more conservation-friendly work. As a result of providence, Foster became close friends with a man named John Wilson who was heading up the American Cave Conservation Association (ACCA).

The ACCA Board in the early 80s, as efforts took root.

Submitted

“John was looking for a person for his staff, so I applied. I went to work as the Program Director,” said Foster. As the Program Director Foster was responsible for putting on cave seminars and workshops for agencies such as The U.S. Forest Service or the National Park Service to help them properly manage their cave systems. Topics of discussion included protection and repair of mineral formations, gating caves to protect them, liability issues and the inventory and protection of rare cave species.

That work went on through the 80s, and in 1987 the American Cave Conservation Association moved to Horse Cave from Richmond, Virginia, at the bequest of community member Bill Austin. The cave itself, prior to being called Hidden River Cave, was named Horse Cave as well, but became Hidden River Cave several decades earlier. It was a perfect fit. Naturalist John Muir had even noted Horse Cave in his writings in 1867. “The entrance (to Horse Cave) seems like a noble gateway to the birthplace of springs and fountains and the dark treasuries of the mineral kingdom. This cave is in a village (of the same name) which it supplies with an abundance of cold water, and cold air that issues from its fern-clad lips. In hot weather crowds of people sit about it in the shade of the trees that guard it. This magnificent fan is capable of cooling everybody in the town at once.”

In the 1930s a staircase that is still barely visible through hillside foliage was the access point for cave tours.

Submitted

A planning grant from the Economic Development Administration provided funding for a feasibility study and Horse Cave seemed like an ideal place for a national cave and karst center. The site was in an internationally significant cave area near Mammoth Cave National Park, and educational and environmental needs were obvious, since it was a history rich, polluted cave smack dab in the middle of town, and in the middle of a tourist-rich region. Although there were many obvious reasons to settle in Horse Cave, there were obstacles. Pollution, resistance to change and funding were some of the stumbling blocks.

“The ACCA had a little money in the bank, but it wasn’t much to start such an ambitious project. The former cave owner Bill Austin once had a talk with Warren Hammock who directed the Horse Cave Theater., and Warren asked Bill how they were going to raise the money for the theater. Bill said, ‘you’re an actor, right? Then act like a fund raiser!’, so that is what I did. I learned how to ask for help and we began raising money to build the American Cave Museum and restore the cave,” Foster reminisced. And there was much to be accomplished. Enthusiastic supporters such as Bill Austin and his wife Judy were an essential part of the project’s development, as was a partnership with the City of Horse Cave.

“The City of Horse Cave owns the cave and museum. The American Cave Conservation Association has a long–term operating and management agreement with the city. It has been a very unique and successful partnership,” Foster said.

“The cave itself was horribly polluted and desperately in need of attention,” Foster said. The pollution was the result of an inadequate sewage system, and industrial runoff from a dairy plant and a metal-plating plant.

“Heavy metals and waste would gather in the setting tanks, and the waste was more than the old sewage treatment plant could handle,” Foster said. With the natural symbiosis out of balance, the restoration was necessary but also out of reach. But, not for long.

A new regional sewage treatment system was soon established by the Caveland Sanitation Authority in 1989, and with sewage no longer draining into the vast recesses of the cave recovery naturally began to occur. Only a few years later in 1992, the American Cave Museum opened, as fundraising efforts for the cave and the land around it continued and advanced.

Since that time approximately 7.5 million dollars of monies have been raised to expand, explore and develop Hidden River Cave.

By 1991, the underground river had taken on enough oxygen to once again support indigenous life. Under the guidance of the ACCA the cave officially opened for short tours in 1993.

“We kept expanding the tour over the next 30 years. We finally opened Sunset Dome in 2020 after five years of planning and construction,” Foster said. Sadly, that development came just in time for the pandemic. However, every clouds has a silver lining, and the monies from the pandemic have enabled the ACCA to do a better job marketing the cave with signage on the interstate so that Hidden River Cave is no longer so hidden from the public.

Sunset Dome is a massive dome, opened to the public in 2020. it is one of that state’s most stunning nature formations.

Submitted

The cave has three separate domes, including Sunset Dome, the largest cave room in Kentucky, the world’s longest underground swinging bridge, and a subterranean river. The cave visit is an enthralling experience for the senses. Dark passages have been well-lit through painstaking measures, the constant rush of the underground river is always present, and cave life is around every dark corner.

In 2013, Dr. Julian J. Lewis began a biological inventory of Hidden River Cave. Dr. Lewis found that the cave is home to twenty-one types of endemic cave species, making the cave a global hot spot of subterranean biodiversity. In two decades, Hidden River Cave had transformed from one of the most polluted to one of the most biologically diverse cave ecosystems in the world.

Although Hidden River Cave has come a long way, Foster is adamant that it has a long way to go.

“There is still much work to be done,” Foster said. “If it seems like I have a chip on my shoulder, this is the reason; Most caves are in rural areas and those of us working with these natural resources have to work exceptionally hard to build public support and awareness of the conservation needs and the scientific value.

But even though we are located in a small town in Kentucky, we still have a world class cave system and our conservation work can serve as a model for communities all around the globe that are built over fragile cave and karst ecosystems.” Foster said.

As for the future, retirement is on a distant, distant horizon. Foster does however feel his life’s work is in good hands, with the steady and encouraging presence of good board members, the support of the city and community members, donors who have left their inheritances to cave efforts and employees who enthusiastically love their work and Hidden River Cave.

He also has the support of local industry, such as DART and others who replaced toxic industries that once polluted the cave and waterways, and now support the community in turn with jobs. Ultimately, the cave that is at the geological center of Horse Cave is also a philosophically central and vital part of everything good, pure and enduring in Horse Cave.

To schedule a cave and museum tour, visit hiddenrivercave.com

To fully understand and appreciate the important role of Hidden River Cave now, and for the past four decades, one must reach further back in history to the early part of the 20th century.

To fully understand and appreciate the important role of Hidden River Cave now, and for the past four decades, one must reach further back in history to the early part of the 20th century.

In 1916, a half mile-long section of Horse Cave was opened to the public for tours. As part of a promotion Dr. H.B. Thomas ran a local contest to rename the cave, and the name “Hidden River Cave” was chosen for tourist use. Although people have always been fascinated by the cave, it is also sadly true that locals didn’t always appreciate the cave.Since the region was first settled residents dumped their trash and injected sewage into underlying cave passages, shallow wells, and nearby sinkholes, with little to no thought of the local water supply. By the 30 the groundwater was polluted to a district degree, and in 1943 noxious odors emitted by the cave’s pollution caused tours to cease, and with the passing of another decade the entire downtown area of shops and businesses were infected by smells in the summer and everything associated with the city became dilapidated.

By the 60s efforts were made to contain the sewage, but resistance from man sources including the railway system, and misguided efforts resulted in another two decades of turmoil surrounding the now beautiful spot.

Comments